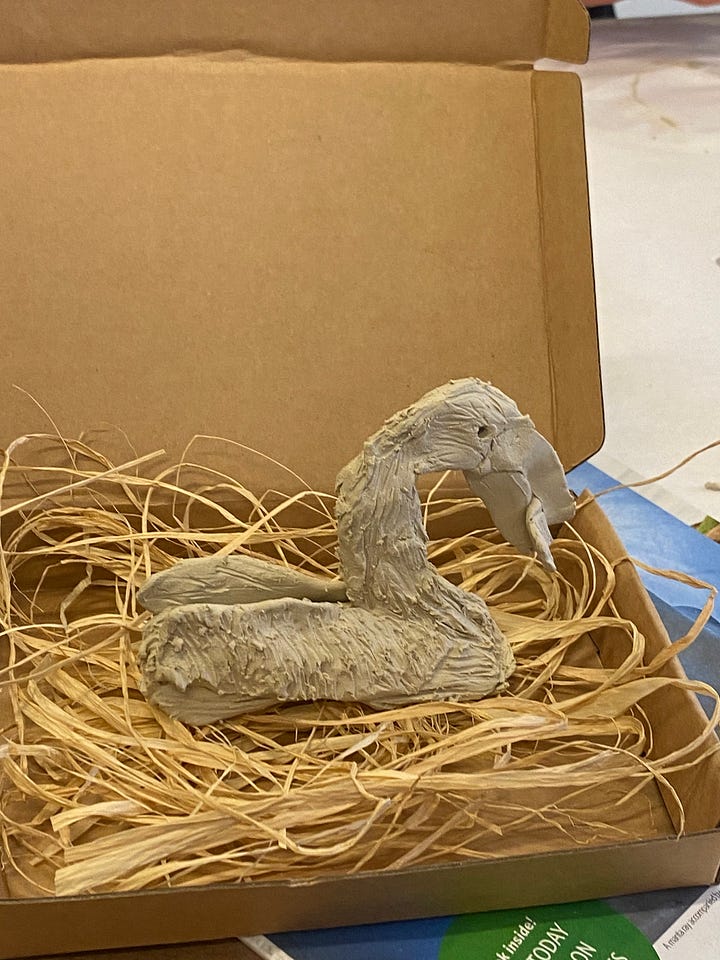

I sit in the museum and make clay birds the size of my fist with a woman I have never met before. We are preparing for a family activity the following weekend: educating children about local bird populations in the lagoon. She is a volunteer and I’ve already been at work for a couple hours. As we sit (she makes a penguin, I make a hawk), I ask after this woman’s art practice, and she tells me she mostly makes work about being chronically ill but sometimes enough is enough. I pull some yarn and raffia out of a plastic bag to start making a little nest and nod my head, understanding.

This week, I have been going through studio cabinets filled with dry and rotting paints, dumping plastic bins into industrial trash bags. I teach one of my coworkers that expired inks smell like buttered popcorn- this is how you know when its time to throw them away. I try to remember all my training from Cass Art in Islington ten years ago about how to dispose of art chemicals and, coming up empty, quietly slip everything into the plastic bags with an apology to the local landfill.

The paint cabinet is piecemeal (one of many piecemeal cabinets, like its neighbor filled with cookie cutters and loose beads- and largely composed of well intentioned donations from strangers. I think over and over again, pulling ancient photo-mount cans out from behind plastic storage bins, I think, I wish I could call my dad and ask him how old he thinks this can is, how he thinks long it’s been sitting in this stupid crowded cabinet. My dad was an artist, but spent most of my childhood working in the art supply business, driving in between stores (once plentiful) across Los Angeles and Orange County. I think, as I pull out ancient products, I think, I bet my dad would know the last time anyone bought this.

Art funding’s been funny this year, and instead of driving back and forth to elementary schools as is my usual daily routine, I’ve mostly been sitting around at the museum, re-drafting family-friendly art write ups in lieu of anything better to do until the government grants start to roll in earnestly. I’m cleaning this closets because I’m itchy without something to do with my hands and I’m tired of cold calling galleries to hunt down information about long dead artists.

My cleanup is mostly routine- dumping out bins of unlabelled containers, separating things we can use for summer camp, but then I find an apron in a pile of aprons from a store my dad used to work with and I have to stare, unfocused, for about twenty minutes to keep it together.

Though the find is mostly innocuous, and not totally unexpected, I am unable to process seeing it. I tear up. I fold it up. My dad had bags and embroidered shirts with this logo on it. He had a lot of shirts from art supply stores and brands- I still wear my Golden apron from the years he worked as a Golden Paints rep. All my brushes are still stored in Windsor and Newton promotional jugs. My sister has a backpack from Macpherson’s that she carries around sometimes still. I probably gave away 10 of these exact aprons when I cleaned out his studio and didn’t even think about it.

I had to call this store to tell them he died. I don’t remember what they said back to me, but I remember it was worried and kind.

It’s just an apron. Still, I’m sick to my stomach, completely stalled in what I was doing.

When the woman I’m making clay birds with tells me that enough is enough, that sometimes you can’t talk about the bad thing anymore, sometimes you have to make art about something else, sometimes you just have to be be something else- I tell her that I understand, and I really do. I tell her about this project and how sometimes I feel like closing my laptop, deleting the files, and just walking away from it. I think, how can I keep doing this, surely I have to be done by now.

But then I stare at an old dirty apron for twenty minutes and spend all weekend shoving wires into a crow skin and think, I don’t know if being done is really on the cards for me. There was a time before my dad died, before my grandmother died, that I could have separated talking about death and talking about grief- one thing I did constantly in my art and academic practice, and another I mostly ignored. They’ve fused, though, now.

A few months ago, Bela wrote an essay about Renato Rosaldo’s “Grief and the Headhunter’s Rage” and sent me the PDF. They talk about me, about death, about death being at the core of their work, about death being at the core of mine. I talked about death before my dad died. I talk about it now, a core issue made unfortunately material instead of theory.

As I pack up to go home from the museum, I slip the Art Supply Warehouse apron in my purse and take it home with me.

xL